Face Shifts in Alain Resnais’s “Providence”

Posted by Raluca Turcanasu on / 0 Comments

This is my academic paper for “Question d’iconographie” at Lettres, Arts et Cinema, Paris Diderot (7) submitted in April 2019, with the prof. appreciation 🙂

“The dream is my only real level of my existence”

Alain Resnais’s “Providence”, 1977, explores the theme of artistic creation in its profound facets, as the author slides from being in control of his work to being under the control of the work, be it wide awake or, mostly, in his dream-nightmare.

Briefly, Clive Langham, a cvasi-famous writer acknowledges his soon-to-happen death and decides to write a final novel (hence the literary use of language throughout the film). Yet, the work proceeds him and arguably embodies him in his sleep, where reality get embroidered with fiction, the fiction of the dream-state, tormenting Clive and revealing the hidden ties between his life and his work. Unknown aspects of his relationship to his wife, Molly, or to his sons, Claud (his legitimate son, a lawyer) and Kevin (his “only bastard” as we find out in the end) are revealed.

In this current paper, I shall underline how such revelations occur through the dispositif of replacement.

The replacement or the face shift, a specific “tool of the unconscious” that acts within the dream-state, stands at the root of the texture of “Providence”, as the characters differ not only when they take a different visual identity but also when they seem stable.

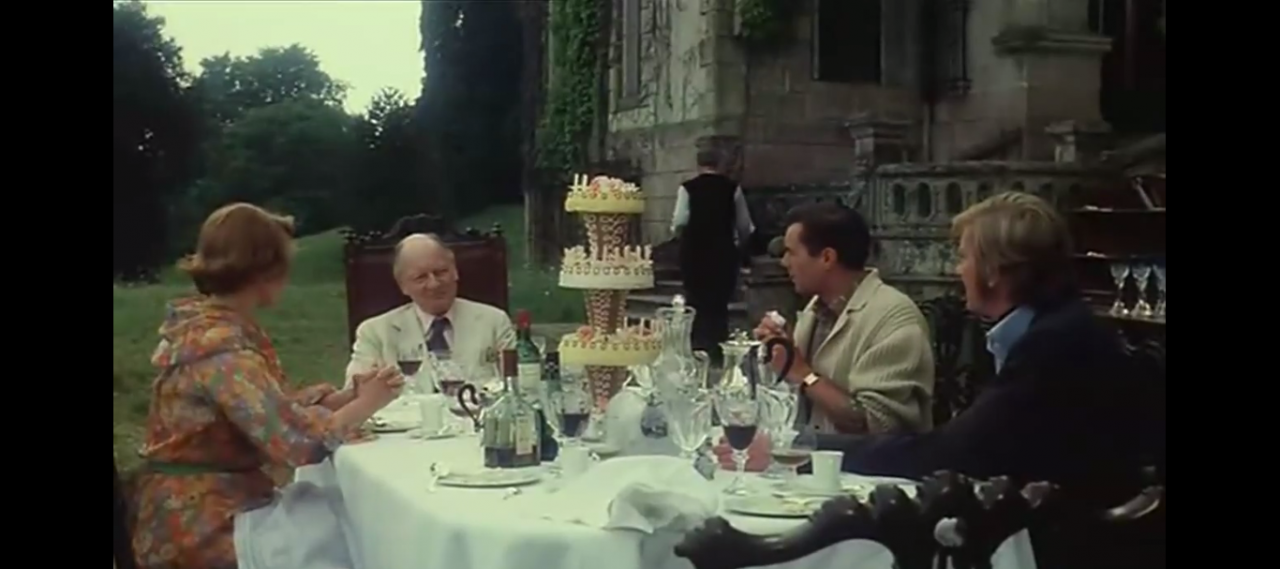

Such would be the case of Claud Langham: portrayed as the legitimate but hateful, cold son, the final scenes, of the 78th birthday of Clive would reveal a rather sympathetic son, a different person then that portrayed by the father.

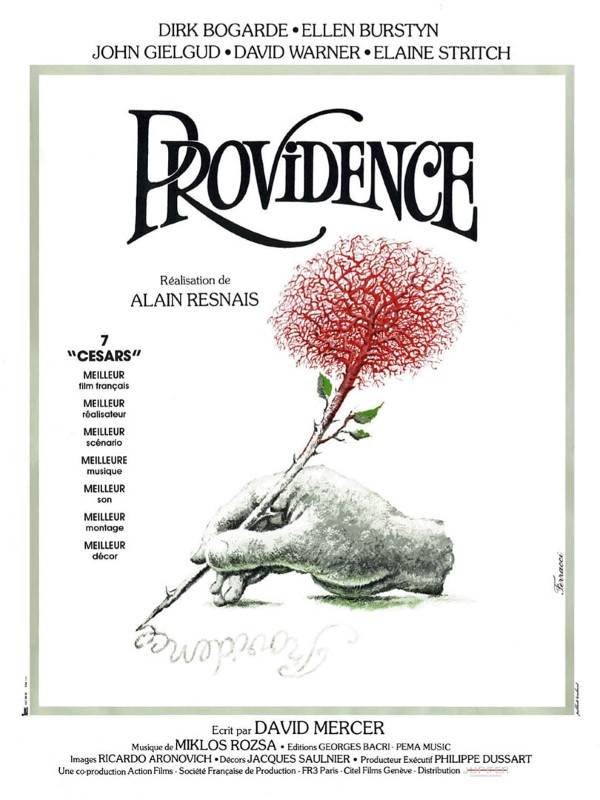

The keen spectator will find out within the first 10 minutes that „Providence” is the story of a process of creation: if too taken aback by the scene of the werewolf (that shall be discussed shortly), he will definitely grasp the idea at minute 9.49, after the court session.

As they go out of the court, we’ll hear an already heard voice (deja-entendu), describing the action, but as a voice-off (hors-champ):

Oh, Sonia, why did you marry that petrified lawyer of a son of mine?

It’s Clive Langhman, the father of Claud. Such remarks will rest with the spectator for the entire film but only at the end will he fully realise that there are two out-of-the-ordinary states put to work: the creative-state and the dream-state. Until the second part of the film, when Clive, Claud, Kevin and Sonia celebrate Clive’s 78th birthday at the Providence residence, it will remain unclear what is dreamt and what is remembered. Some argue that even this second part is still within the dream[1], while making the point that it is the space of action that conserves, to some extent, the coherence of the narrative.

In what follows, I shall proceed into analysing the face shifts and metamorphosis of the characters and retain the idea of spatial coherence.

Before plunging into such analysis of this filmic-nightmarish transformation, we should note the dream imagery that functions as a frame for those face shifts. The face shifts are in fact part of the dream experience and, along with the following other elements, define the dream logic, the nonsensical knowledge one possesses while dreaming, that makes perfect sense until he or she wakes up. It incorporates a collection of things on the periphery, things that point to other things and incorporate elements of the familiar, but in odd, skewed, haunting or even disturbing ways. To define this skewed universe, I shall briefly provide some examples of its skewed imagery, which functions as space metamorphoses:

1/ The hotel in which Claud meets Helen changes its layout from one scene to the other: in one scene the bedroom is at a second floor, whereas the door is on a lower floor, in the second scene they are on the same level.

|

|

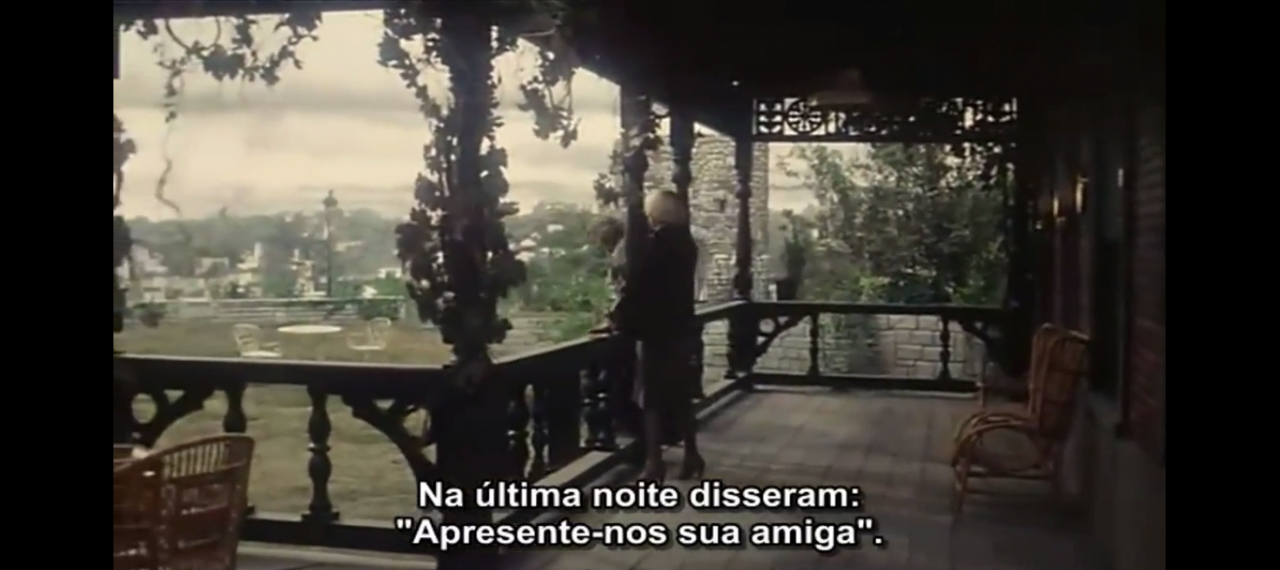

2/ The “Providence” residence as a common thread between the daytime stories of Claud, Sonia and Kevin and night-time story of Clive. Several elements point out that all depicted houses are in fact the same one, a common dream experience of representing a thing as something else, yet still knowing what it is, even when it appears in a morphed aspect.

What one can see in the above stills is the repetition with a degree of difference: using the same framings (with one exception), what differs is the setting, as if the house had travelled to a faraway land.

1) The first one (1 – minute 42:49 – 44:00) is set on the coast of a sea with pine trees and agaves and, narrative wise, it presents a dialogue between Claud and Helen on how it would have been for them if Claud wasn’t already married to Sonia.

|

|

In the meantime, in an uncanny manner, Sonia is in the living room, taking care of Kevin’s wounds. What’s also relevant in this scene is Claud’s last line, to Helen: “How you and father would have fought!” which functions as a sign for the manner in which Clive’s persona, that is the dreamer’s, reverberates into the other characters.

2) The second instance of the house porch, the déjà-vu (2 – 1:06:25- – 1:08:13) not only features the change of scenery, in this case closer to the real setting of “Providence” manor, but also the replacement of Claud by Kevin.

|

|

The scene comes right after a night wake up of Clive, and his war time memories still echo into the other world: Helen is looking in the distance, listening to the bombings. She says to Kevin:

I thought you might come to see me.

as if she is at her place, but the place looks like Claud’s/ Clive’s place. She acknowledges the morbid attraction Kevin has for her and the white wine:

Claud always drinks white wine (…) When you love someone, you’re sensitive to their tastes. It’s rarely mutual. And that’s because one is rarely loved.

But in fact it is especially Clive who always drinks white wine, even as he wakes up in the middle of the night and Helen will continue to talk about Clive:

“When you went away to school I was desolate. One of the childishly insulting games was to pretend I wasn’t there. That he didn’t know me. He was giving some lectures once in Vienna and he didn’t introduce me to a single person in 10 days! It was the big public reception on the last evening, and someone said: “Why don’t you introduce your friend?”. He just turned and starred at me in silence, I was just drowning with embarrassment. He said “I haven’t the faintest idea who she is”, he said to me. I haven’t the faintest idea who she is! I think you noticed everything. No wonder you became a remote little boy and grew into a cold heart young man. I began to loathe you as much as I feared him”.

At this point the spectator is left abashed: is Wooders the brother of Claud, while having been prosecuted by Claud, while Sonia, Claud’s wife is in love with him? In fact, as we are in the dream-state, Kevin might not exist at all in this shape, he could very well be a figment of Clive’s dream, invested with his repressed guilt and fear. The hypothesis is justified by the mere words of Clive, in the first minutes of the film (00:15:16):

I once had a fatuous life, I might as well have fatuous nightmares, but I am frightened.

3) The third instance of the house porch features Claud and Sonia and it takes place again in a marine setting, but a different kind of beach, one with less vegetation and white sand. Here the framing of the table is missing and the porch has become white and even has a hammock, to match the seaside architectural cliché.

|

|

As the film advances and the unheimlichkeit with it, the connection, the “raccord” between the previous scene and this scene is even more uncanny than before and I find it worth mentioning, to note how destabilising for the narrative such déjà-vus are.

Minute 1:12:50: Claud is following Kevin with a gun pointed at him. They enter the mansion, but inside it looks like the restaurant from the beginning. Claud loses Kevin: there are just two other man having dinner. He gets out of the room only to enter another room, which is the same as the room he had left!

Minute 1:12:56 |

Minute 1:13:11 |

The déjà-vu deepens, it is stratified (a mise-en-abyme of déjà-vus) as Claud finds his wife and Kevin. Sonia introduces Kevin and Claud plays along:

How do you do?

“Not very well”, answers Woodford,

I think something must have gone wrong at an earlier stage. It could be childhood. But then I don’t suppose we could spend the rest of our lives attributing it to that. What I’m searching for, Mr. Langham, is a moral language.

A third layer of the déjà-vu emerges, as this moral language is what we know Claud was aiming for. An abrupt cut and the earlier scene is replayed a third time, Claud goes up the stairs, gun in his hand, but this time he exits on the white, seaside porch. He finds Sonia who tells him:

If I don’t leave you, I’ll probably make you suffer for it, you understand?

Yet, their following question is again a reverberation of Clive’s unconsciousness:

Sonia: What is this huge huge feeling of emptiness?

Claud: A complex. Yours is the misery of triviality.

Sonia: And yours?

Claud: I don’t suffer.

How could the misery of triviality not be Clive’s complex, when he himself would remember in the wake of the night (minute 35:06):

Why haven’t you got the Nobel prize, daddy? Our English master says you aren’t nearly as good as Graham Greene… I wonder why Graham Greene hasn’t got the Nobel prize either.

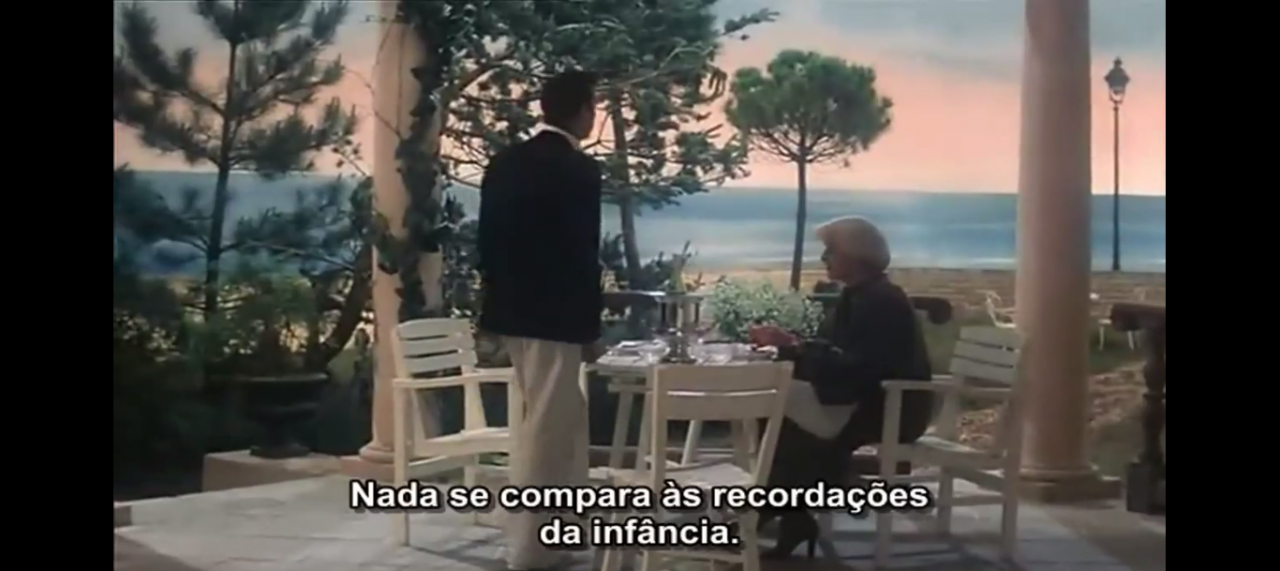

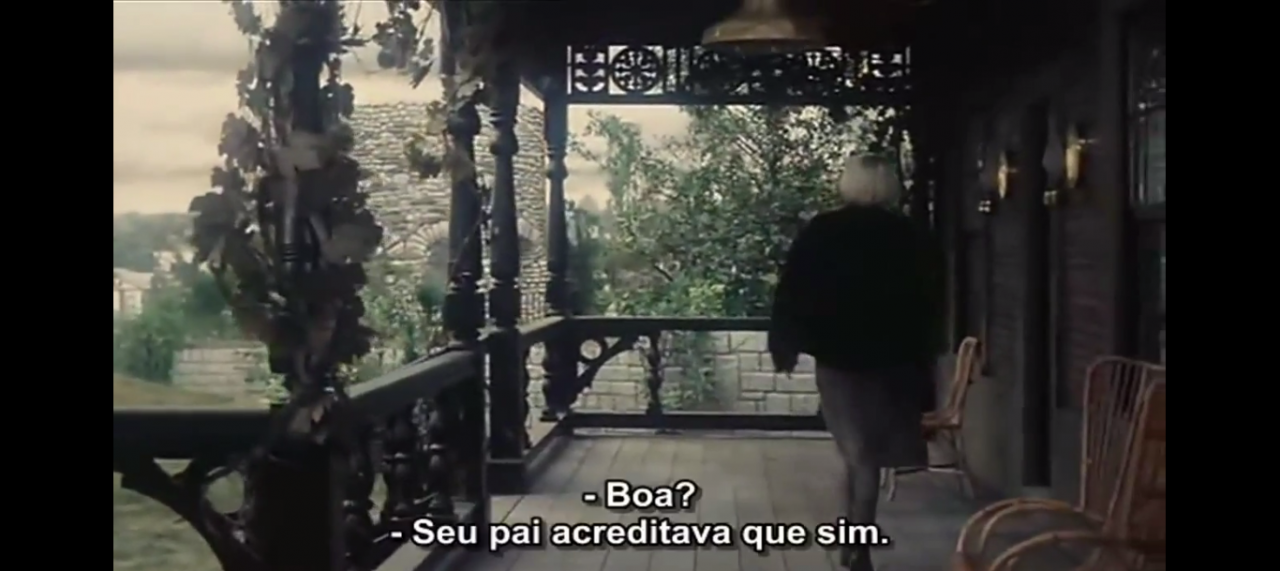

4) The fourth and final déjà-vu of the house porch is somewhat of a prolongation of the second scene, a bizarre sort of „endo-montage”, only that Helen is talking to Claud this time.

|

|

Helen: I simply wondered whether my arrival might provoke some sort of crisis in your life.Claud: You think a crisis would be good for me?

Helen: Your father thought so. I cabled him. This is his reply: Death no problem. STOP. My son an emotional cripple. STOP. By all means, descend on him, if it will amuse you. STOP.

Claud: Set and game to father.

And, awakened, Clive repeats: “Set and game to father”: a metaphor coming from tennis suggesting the stratifications of memory, of consciousness and life as a whole, as if Clive has won the game, the set and is soon to win the tennis match.

Thus, Providence”, the manor, can be interpreted as

a stratified location in which energy takes a regressive direction; movement is from the conscious and the preconscious to the unconscious, passing through the frontiers of censorship [2],

as argues Laura Rascaroli. Indeed, the camera movement in the first scene points, in its eeriness, to this transition through the layers of the consciousness and can function as a key to interpret the film.

Such movements through the same yet always skewed residence (the house and its exterior surrounding) can work as a sign of the psychic movement within the fictionalised drama of the memory.

The fictionalised memory can and is embodied by all the characters, in a stunning “set and game” in which the subject will endorse all the roles[3].

Following the latter remark, my proposal, for which the above-mentioned description of the metamorphosis of the house, is to consider the Providence manor as an extension of the dreamer-creator, Clive Langham, and the other characters as embodiments of this overarching creator, one who stands taller than Clive himself, as he is able to mutate Clive’s narrative and to even project undesirable images onto Clive’s mental screen, to use a deleuzian formulation.

As Resnais himself has recognized, Clive comes more and more to resemble a (Freudian or Lacanian) dreamer, who is at the same time the creator responsible for the events in his dream and the passive spectator of the images imposed by his unconscious [4].

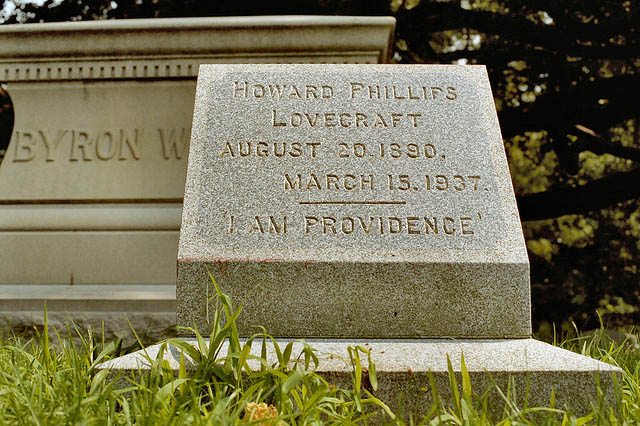

Regarding the house as emanation of the unconscious, “Providence” is most probably a tribute to HP Lovecraft, who would write, in a letter to James Ferdinand Morton:

Regarding the house as emanation of the unconscious, “Providence” is most probably a tribute to HP Lovecraft, who would write, in a letter to James Ferdinand Morton:

“I am Providence and Providence is myself – together, indissolubly as one, we stand thro’ the ages; a fixt monument set aeternally”.

It, hence, can very well be a tribute to the very idea (of Lovecraft) of the house as part of one self.

The multiple faces of Clive Langham

Building on the previous idea, if the “Providence” residence is an emanation of the authorial unconscious of Clive, I shall argue that, to some extent, the characters are, too. The fact that the main part of the film is actually a dream and a nightmare, Clive’s, implies that Clive’s unconscious might very well identify with any of the characters. Or, to fundament this more theoretically, I would appeal to Ludwig Binswanger’s psychanalytic daseinanalyse theory:

What characterizes the dream very precisely is, as Sartre emphasizes, the fact that the dreamer has an emanation relationship with the dreamlike hero with whom he identifies, which explains why he can feel himself as identified with someone who is yet outside. The specificity of the dream world is due to the ambiguity that makes it both a representative world and therefore outside the dreamer who contemplates “from above” and a world immediately lived in which the dreamer feels immersed [5].

Binswanger’s theory seems suited to explain the ontology of “Providence”, as a non-devisable entity in dichotomies such as subject-object, dreamer-dreamed of, wake-asleep, given the fact that this theory discusses the dream as an ontological process itself (and what is “Providence” if not the world born of a dream), beyond a psychological one. What’s also important is that the German psychanalyst discusses the human being as non-detachable entity, up to a certain point the human is regarded as a part of the ontological wholeness, thus being non-autonomous.

Considering the evolution of Clive (or of Clive’s dream), through his remarks both in his nightly wakes and as authorial voice-over, we can see this theory at work, cinematically: the characters overtake him, his dream or his creative voice imprints him more than intended.

To quote some examples, even in the beginning, when Clive still maintains some sort of control, we have the scene with Dr. Eddington sent off by Sonia to the restaurant, and Clive as voice-over:

What are you in my scheme of things, Eddington? A Jolly old. Bloody old doctor character. God forbid! Never liked you, Eddington! Never understood what Claud saw in you! I’m getting rid of you at once.

Even from this point he seems not to fully grasp the evolution of his creation. Or, more accentuated as the film advances and the dream/the creation become more autonomous, at minute 1:08:13:

Clive: Will you kindly get out of my mind, Molly? Will you, please, stop interfering with my last feeble efforts?

Hence is his non-autonomy, the way in which Clive is defined by his work (and his dream), in an equivalent manner that his work (and his dream) is defined by Clive.

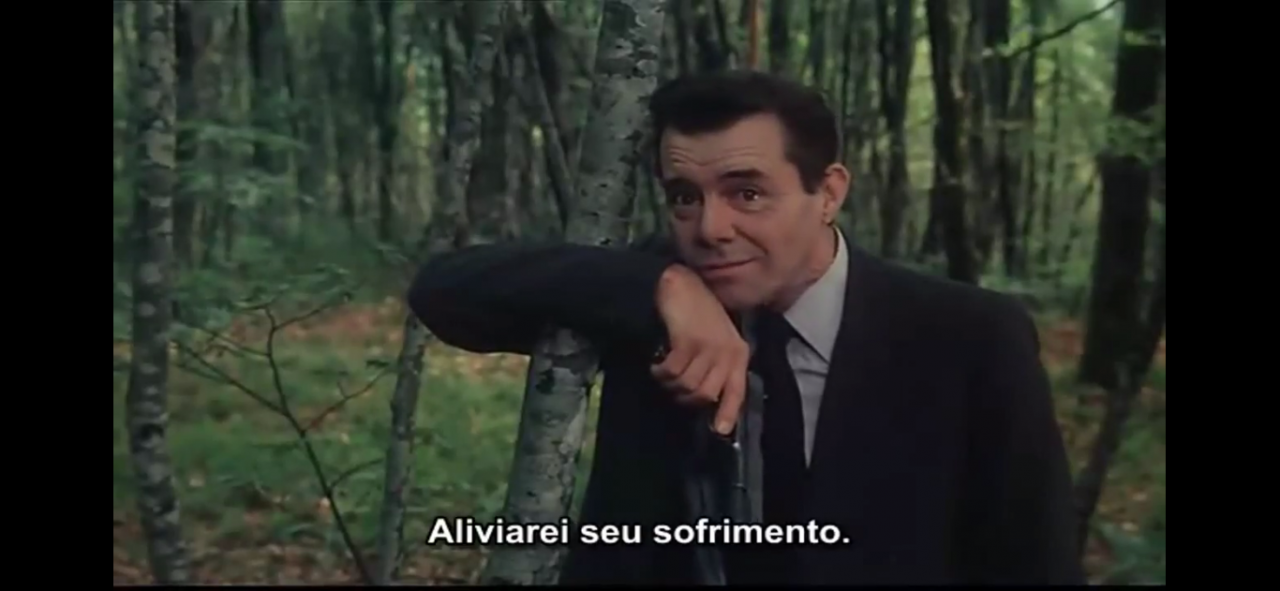

One shift, even though not yet a facial one, that operates on the above logic happens at minute 00:20:38 when Sonia suddenly gets the voice of Clive and says to Kevin:

Why are you so obsessed with those bloody astronauts?

She realises her mistake and, just like taking a double, she redoes the scene, in a more pleasant voice, her own. The character retains the traits of the creator-dreamer, who embodies her, for a very brief second. In fact, it is the same process that defines the film and which is especially visible each time Clive repeats the voices of his characters, such as when Claud is going to meet Helen and Clive is thinking for and through him (minute 00:27:15):

Who does not know the mix of fear and excitement of going to meet an old flame?

when Sonia’s tears become that of Clives, superposed on the war imagery (minute 00:37:10), or when Claud says “I feel nothing at all” and, directly cut, Clive approves: “You can say that again” (minute 00:34:34).

The over literary choice of words of the characters also suggests that they are just various embodiments of Clive, such as the case of Sonia saying:

I’m more interested in how he fornicates.

and Clive repeating the same phrase and laughing of his own creative game (minute 00:57).

Some other times the embodiment comes through only by the choice of words, without being underlined by a vocal repetition. Such is the case of Clive saying:

It was said that my work in the search for style has often resulted in a want for feeling.

at minute 00:31:45, a critique received by Clive the novelist, but also by Chris Mercer, when his plays slided from the political into the personal and became more self-reflective.

It is Bergson theory that sheds some light on what happens with Clive:

the individual splits in two different characters: one who is the “free spectator” facing the scene; the other “the automatic actor” plays mechanically his role, repeating entirely things already said [6].

It is often that this process occurs for Clive: watching first his characters play and then repeating their lines, laughing or challenging them in a certain way.

In fact, all the characters are parts of Clive or partly Clive: definitely the males, whose names even sound similar to Clive, all starting with the sound /k/: Claud, Kevin, but also Sonia or Helen, who often think, say or do things that only Clive would. This is the fundamental law that governs the face shifts of “Providence”.

There is a dissolution of Clive’s ego that is thereafter absorbed in various proportions by the other characters. In a Freudian perspective, we can consider Kevin as the animal, the instinctual layer of Clive, the id. Resnais himself has described Kevin as “closer to nature, to the animal”, which is underlined by Kevin never leaving his clothes (his skin) – throughout the dream he is always wearing the same neck sweater.

Claud, the prosecutor, personifies his father’s bourgeois, conformist and moralist side that he himself questions, as underlined also in the final scene, at the table, minute 1:35:00.

Clive: A bourgeois is merely a man who refuses to accept the ideological news

Claud: No, father, no. The bourgeois is only the man who understands the ideological news as the death of his values. I suppose I’m one of them. I don’t know if my values are correct or incorrect, they are just the moral structures by which I live.

Claud is the punishing super-ego of Clive and constantly puts him to scrutiny, even in the above mentioned dialogue in the wake of the day.

In this respective, it is interesting to note the living-room scene, in which Claud, the super-ego, tells Kevin, the id: “Don’t fall asleep! I know you have inner peace!”. The super-ego tries to restrict he id, for which every impulsive need or pleasure should be accomplished directly, disregarding the consequences, but not in the expected “healthy way” – for example Claud does not do anything to stop Kevin from engaging into sexual relations with Sonia (he even encourages it by attempting to send them off to a far-away city) – but by not allowing him to sleep, to go absent. It could be a cry of need of the super-ego to the id, who has reached inner peace.

What drives such embodiments and causes the disturbances is either:

a) the compulsion to reiterate death – as memories and as psychological drivers, or

b) sexual compulsions repeated in an Oedipal manner, as a “compulsion of repeating childhood’s games”.

Following this, a second face shift needs discussing: that of Molly-Helen, because it works as the common thread between the two aforementioned drives of the unconscious.

This somewhat collective character, Molly-Helen, encompasses the Eros and Thanatos of Clive, stands at the intersection of fear and passion, of desire and anguish and reiterates the idea of the non- dichotomous approach of subject-object.

Helen, the random cast that Clive chooses for Claud (in the airplane, minute 00:18), mirroring in his son his own compulsion to have extra-marital relations, looks exactly like Molly, the mother of Claud and Clive’s wife. But Helen is also the mother of Kevin, as it turns out from their talk, on the porch of the house, mentioned before or from Clive’s remark “How you and father would have fought!”. Both Kevin and Claud are attracted to their mother(s). But it’s in fact Clive’s unconscious that operates from three directions:

1/ his own Oedipal complex shines out to define his two boys, as he even judges Claud’s attraction to Helen (minute 00:30:41, “She looks like his mother” says Clive as voice-over, even though he had chosen Helen for Claud’s mistress:

Clearly the boy must have an unconscious mind, just like everybody else.

2/ his remorse and self-guilt regarding the suicide of his Molly,

3/ his insatiable sexual desire. The latter embodies Kevin, the id, in a carnal manner, as he has an erection which is not his own (minute 00:56), right after having mentioned Molly’s gloves and then not having remembered his own words.

Claud, the super-ego, comes to explain what had happened to Kevin:

Do you know what resembles the older Langham? He always sprang random erections, that’s one thing I do know.

In fact the “I don’t remember” line works as a cinematic mark of such a ghostly embodiment of Clive in Kevin and Claud. To Claud it had happened before, also when Helen had called – repetition with a slight difference of the same process of embodiment, generated by reminiscent carnal desires of Clive, who now relives such passions by embodying his sons in his dream. Claud had talked to Helen over the phone, they arranged their meeting and, after hanging up, Sonia asked “Who is Helen?”. Yet, ignoring the question, Claud turns his attention back to Kevin: he is more interested into the depth of his self, his id, which the super-ego deems unworthy, not enough. The passion, the “object of desire” of the id so to say, is futile, obsolete, has no real importance, as he forget who Helen is the moment after.

All seem symptoms of the pressure of a massive trauma which has not been well assimilated by Clive: the trauma of the war, represented by the nightmare visions of those (fascist) imprisonment camps in which Molly, Claud and Sonia, in turn, get caught (a cinematic déjà-vu of Resnais’s Nuit et Brouillard); and the trauma of Molly’s suicide, partly accepted by the id which “has inner peace” partly still causing a great deal of sufferance, regret, self-guilt.

There is a definite trouble of the super-ego, whereas the id is at peace. It is Claud that Clive always argues against, is condescending about. From a Jungian perspective, Claud could in fact be the shadow of Clive, the accumulation of traits that Clive does not like about himself and, without willing to deal directly with his own shadow, he projects it onto Claud. Of course, the characters are much more entangled than that and arguably Claud could also be the persona, the outer mask, in the Jungian approach. Yet, it could be very well that Clive does not dream of his persona, his worldly identity – mask, because he is quite satisfied with that (simpler put – Clive is the persona, the tip of the conscience ice-berg).

However, to close the discussion on the collective character Molly-Helen, I would argue that this collective character actually includes Sonia as well. Within the dream, they are all unconscious representations of the anima of Clive, he projects his inner anima onto them, equally within the dream. He blesses Sonia, anima, to have sexual relations with Kevin, the instinct, the id, she has her protect him in front of Claud’s tirade of accusations in the kitchen or, in the final scene, he has her in sort of a kneeled down position, docile and wise, while they talk, on the day of his anniversary. This is furthered backed by Sonia saying:

I’m not a person, I’m a fucking construction!

– the construction of Claud, her husband, the construction of Clive, the dreamer, the construction of Resnais and Mercer, the creators outside her filmic matrix.

The third and most striking face shift is that of Kevin the military to Kevin the werewolf.

1: In the beginning, minutes 07-08.00

|

|

2: Minute 29:15, the werewolf is seen by Claud, as he drives to meet Helen

3: Minute 1:17:20, Kevin has become the werewolf:

|

|

The initial scene, especially set at the beginning of the film, is troubling enough for the spectator, but when it occurs again and again it becomes truly disconcerting and one is left pondering what should make of it. This face shift happens gradually, as Clive-the dreamer goes deeper into his unconscious state and it is intermediated by the overarching theme of “every man should die the way he chooses”.

This is the aggression, the mortuary side of the id, Kevin, and at first he is at the active pole: he is the one to take out the first werewolf, then he goes through the declarative state, when he installs a large banner on the columns of a public institution and is caught by the gendarmes, ending in the passive state: being himself the werewolf who gets killed by the super-ego, Claud, and in the garbage bin by the militaries.

According to Binswanger’s theory, it is:

a metamorphose of the existence that is the psychosis by which the patient is mainly experiencing a transformation of his space [1].

As discussed above, as the film advances the spatiality becomes more and more fluid and confusing but, throughout, it is still Kevin, the id that rests coherent, strong, unchanged. It is also him that comes up with the explanation, so simple that one should not linger on to much: “I think something must have gone wrong at some early stage. It could be childhood. But then I don’t suppose we could be spending the rest of our lives attributing it to that.”

There are several aspects needed to be taken into account for this particular face shift:

i) the meaning of the werewolf,

ii) the tri-phasic transformation and

iii) the correlations between this becoming and un-becoming, that is dying.

Yet, we will discuss the second and the third points as an ensemble, given that they are part of a process, of a phenomenology of becoming or transforming.

i) The wolf has been a symbol of folklore and mythology across the globe for centuries: from Osiris presenting himself as a wolf to Zeus of Lycaon to Romulus and Remus. The wolf has very often been part of a mythology of death: for example, in Ancient Egypt Ap-uat, the wolf-god, would guide souls to the other side, the Greek god Hades would often be depicted as wearing the skin of a wolf or in Rome the wolf would be the sacred animal of Mars, also a god of death. Yet, the agility and rapidity of the wolf also linked him to the creative power of sun and light and, later on, attached a phallic meaning to this symbol. If there are abundant myths regarding the wolf, the same can be said for the werewolf, closely tight to vampires or witches in many legends. It was believed that werewolf had an obsessive voracity, an insatiable lust to devour other animals or people; he would haunt fields or forests during the night and long intervals of lucidity could pass between the transformations. A person could become a werewolf by misfortune or by his own sins.

What is particular in the werewolf transformation in “Providence” is that none of the three werewolves has a voracious need to kill and eat other animals, they are quite calm, they have accepted their condition: the first seems to want to end it, asking Kevin to kill him, the second is debilitated and transported into a wheel chair whereas the third, Kevin, does not want to die but does not present any sign of violence.

I would argue here, from a psychanalytic perspective, that it is Clive’s unconscious struggling between the fear of dying – which his ego has overtly mentioned in one of his night wakes (“Molly if you’re out there in cosmic the dark somewhere, don’t wait for me, I’m not coming”, minute 00:38:54) – and the death drive, that acts for each and every one of us.

The werewolf can be, in fact, regarded as a symbol of the death impulse, as we learn from W. Hertz:

In the Christian era, at the same time with the belief in sorcerers, took of the idea of humans who, driven by a pure desire of murder, used Satan’s help to transform into wolves. The werewolf became, thus, in a sinisterly poetic symbolism, the image of what is animal and demoniac in human nature, of an insatiable egoism, enemy of the entire world, which inspired to pessimistic spirits, ancient and modern, the though proverb: ‹ Homo homini lupus ›”[8].

And what is this 19th century description, written even before Freud’s Traumdeutung, other than very well fitted to the bitter old Mr Clive Langham? All the film and the characters, emanations of Clive’s unconscious, point to him being of “an insatiable egoism”, not caring for the others at all. Even the final “awake” talk proves the same:

How’s the new book coming along, father? Who are you disembowelling this time?

Hence, Clive Langham was infamous for murdering, dissecting his characters. This subconscious self-awareness of being a “Homo homini lupus” could be the main psychanalytic symbolism of the werewolves in Clive’s sleep.

Another key of interpreting the werewolf would be tied to the war and imprisonment recurrent nightmare imagery, which references the Nazi concentration camps. After having lost the war, some partisans of the Nazi ideology became some sort of mercenaries for the cause, trying to callously take out militaries of the Allied forces or Germans who did not support their mission. They called themselves werewolves and their mission was after the war was over.

The reasons for which this werewolf transformation spans around Kevin is quite obvious considering the psychanalytic interpretation previously carried out. Kevin is the dream equivalent of the id of Clive, that responsible with sexual and aggressive impulses. He was born out of a sexual impulse, he’s Clive’s “only bastard”, and he is not ashamed to admit he views Kevin as close to an animal:

I signed a piece of paper, like a dog licence,

says Clive to Kevin on the day of his birthday (minute 1:24:21). In what follows I shall continue to discuss this process of becoming or the transition from active to passive.

If in the first instance it is Kevin – the id – who accomplishes the desire of death of the werewolf, in the last one, a reinverted déjà-vu shot in a very similar manner, in the same spot in the forest, it is Claud – the super-ego – who kills Kevin. But these roles are mixed up between themselves, as Kevin is the one abiding the moral law of “everyone should be allowed to die they choose”, while Claud is the one looking for a moral language.

A possible interpretation could be that the werewolf is the dream representation of Clive’s shadow, which he consciously denies, and which he needs eradicated. The shadow still comes back after having been killed by Kevin, in the form of the derelict old werewolf in the wheelchair. Thus, the super-ego pursuits the hunting of the shadow and strikes to the root of the conscious: the id. As Eros and Thanatos, creation and destruction, life and death are inseparably tied, it could be a desire to reinvent himself, to rebirth in a sublimated conscience, thus stemming again from the profound self-guilt that affects Clive.

Yet, pursuing Freud’s and Schopenhauer’s theories of life and will, it is interesting to note that it is Kevin who is killed, the one who never willed anything in particular, who was not interested in his whereabouts. Hence, if the death drive is the psychological negation of the will, the death of he-who-willed-nothing becomes a profound immorality, the sheer expression of Clive’s egoism, of himself trying to destruct his shadow and instead making it much greater (as to kill a shadow one must bring it into the light, into the conscious). If he was in a search of a moral language, he could have found it through his id and the freedom of allowing people to die the way they choose (or live, for that matter). But subconscious-Clive disowns it and what could have been his opportunity of transcendence to a higher, more profound level of existence is not fructified and leaves him spinning in nightmarish circles.

Yet, considering the lack of time linearity within the dream, we should also take into account that these events could very well be organised the other way around… from end to start. As his life approaches its end, Clive goes through a ceaseless process of becoming: becoming his own child, becoming-animal, becoming-wolf, even though part of him refuses this process. His becoming “lacks a subject distinct from itself”[9], but this subject becomes vivid in his dreams, where the face shift is real.

The non-linear dream reality defines the reality of the becoming,

the Bergsonian idea of a coexistence of very different “durations, superior or inferior to “ours,” all of them in communication [10].

“The Wolf-Man fascinated by several wolves watching him. What would a lone wolf be?”[1], rhetorically asks Gilles Deleuze.It is, in fact, that in his solitude, in his dream, Clive constructs his interior pack, his inner multiplicity that consists of all the characters. His real-life family ought to be his pack, but he reconstructs it unconsciously, from inside out, and, thus his multipliers, all the Clives that inhabit him are rendered corporality in his dream.

Deleuze goes on to cite HP Lovecraft, just like Resnais has celebrated his work with “Providence” and this quote is very relevant for what happens to Clive: it is the story of Randolph Carter:

“who experiences a fear worse than that of annihilation. (…) Merging with nothingness is peaceful oblivion; but to be aware of existence and yet to know that one is no longer a definite being distinguished from other beings,” nor from all of the becomings running through us, “that is the nameless summit of agony and dread.” [12]

It is the same destructive fear that Clive experiences in his nightmares, as he admits to himself (cited above) and the same dread of the undistinguished “cosmic dark” where he does not want to join Molly. Of course, for such an epitome of egoism that his character is, Clive would not want to flee into the undistinguished.

The final face shift I would like to briefly mention as a further development of the processes already discussed (fear and drive of death, lack of time linearity, mortuary dream) is:

Clive and the dead old man being autopsied

The old man is the embodiment of his fear of death and, on one hand, the fact that he dreams himself dead is a sign of his death impulse, whereas, on the other hand, the fact that he tries to cast out the doctor doing the autopsy suggests his refusal to leave his current reality. And yet, even if Clive had already removed the doctor from his story, in the beginning (minute 00:11) he still pops up uninvited, just as a vision, without saying anything, and, even more, while Clive is (at least apparently) wide awake.

Conclusion

To sum up, all the face shifts we have seen are Clive’s multiplicities, conscious or unconscious facets of him that, within the dream space, coexist in various ways in the oneiric universe, in a deterritorialized space that conserves elements from the brick-and-mortar “Providence” but transcends it.

Providence itself unfolds its play in which Clive and all his embodiments have their parts that often overlap, without the possibility to constrain them into classicized psychanalytic theories. The film is a metaphor of creation and disintegration, the creation of a novel from painful autobiographical memories, the disintegration of an imaginary city gradually invaded by vegetation, trees, eaten by worms, invaded by soldiers and gradually destroyed by explosions, while men experience a constant becoming, as re-embodiments (voice shifts, face shifts, entire body shifts) and, furthermore, return to the state of nature and animal. If the film explores the process of literary creation, it is also a plunge into the intricate mechanisms of the unconscious, which cannot be simplified to mere Freudian trichotomies.

“Are we what we think we are or do we become what others make of us in their judgement?” resumed Alain Resnais his “Providence”, in an interview.

I find it worthy to leave you, the reader, pondering on this aspect, while also reminding him or her that such dichotomous choices are always part of a larger, more encompassing wholeness.

[1] Laura Rascaroli (2002) The space of a return. A topographic study of Alain Resnais’ Providence, Studies in French Cinema, 2:1, 50-58

[2] Idem

[3] Arnaud Diane, op. cit, p. 16

[4] Idem

[5] Françoise Dastur, Forward to « Reve et existence », original quote : “Ce qui caractérise très précisément le rêve, c’est, souligne Sartre, le fait que le rêveur entretient avec le héros onirique auquel il s’identifie un rapport d’émanation, ce qui explique qu’il puisse se sentir lui-même comme identifie a quelqu’un qui lui est pourtant extérieur. La spécificité du monde onirique tient à cette ambiguïté qui fait à la fois de lui un monde représente et donc extérieur au rêveur qui le contemple « de haut » et un monde vécu immédiatement dans lequel le rêveur se sent immerge“.

[6] Bergson Henri, Le souvenir du present et la fausse reconnaissance, Paris, PUF, 2012, apud Diane Arnaud, op. cit, p. 16

[7] Binswanger, Reve et Existence

[8] W. Hertz, Der Werwolf, Beitrag zur Sagengeschichte, 1862, p. 14, apud Jones, op. cit, p. 142-143. Personal translation from French. Original citation: „A l’ere chretienne, alors qu’on admetait l’existence de dieux paiens afin de les definir comme diables […] prit naissance, avec la croyance aux sorcieres, l’ide d’hommes qui, pousses par un pur desir de meurtre, utilisaient l’aide de Satan pour se transformer en loups. Le loup-garou devint donc, dans un symbolism poetiquement sinistre, l’image de ce qui est animal et demoniaque dans la nature humaine, qui inspire aux esprits pessimistes, anciens et modernes, le dur dicton : « Homo homini lupus ». » | The latin expression means « The man is a wolf for the man ».

[9] Deleuze, A thousand plateaus, p. 260

[10] idem

[11] idem

[12] Idem. P. 240