FREIHEIT! A good November to visit the Novembergruppe retrospective exhibition at Berlinische Galerie

Posted by Raluca Turcanasu on / 0 Comments

‘ve just visited the Berlinische Galerie, especially for the FREEDOM: THE ART OF THE NOVEMBER GROUP 1918-1935 Exhibition and I really must say it is very well curated and it portrays a vivid and in depth (yet succinct) scenary of the Berlin avangardes of the time.

I will do my best to re-curate it here in educational purposes only, dedicated to young curators and those just diving in the world of art history.

© mentions:

- The following texts belong to Berlinische Galerie.

- The photos belong to me and can be used within the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike framework.

From 1919 to 1932, the November Group produced almost 40 exhibitions, published publications and held concerts, readings, festivals and costume balls. Thus, the group became on many levels to the art mediator of modernity and made for conversation and fierce dispute.

With 119 works by 69 artists, including 48 paintings, 14 sculptures, 12 architectural models and drawings, the Berlinische Galerie is celebrating the 100th anniversary of the most famous unknown creative community in this dramatic first with this very first comprehensive overview show.

When you first enter, you’ll encounter another small exhibition: Julian Charriere’s, “As we used to float”, a journey underneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean.

But let’s move on to the Novembergruppe…

Prologue

By the end of the First World War, more than two million people had perished on the German side alone. The war-weary population was suffering from hunger and deprivation. In autumn 1918, sailors in Wilhelmshaven and Kiel refused to put out to sea for an “honourable” last battle. This mutiny rapidly spread across the country. Workers’ and soldiers’ councils seized power in big cities.

On 9 November the revolution reached the capital, Berlin. Chancellor Max von Baden took it upon himself to declare the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II. A few hours later, the republic was proclaimed – twice, in fact: once by the social democrat Philipp Scheidemann and once by Karl Liebknecht, leader of the communist Spartacus League.

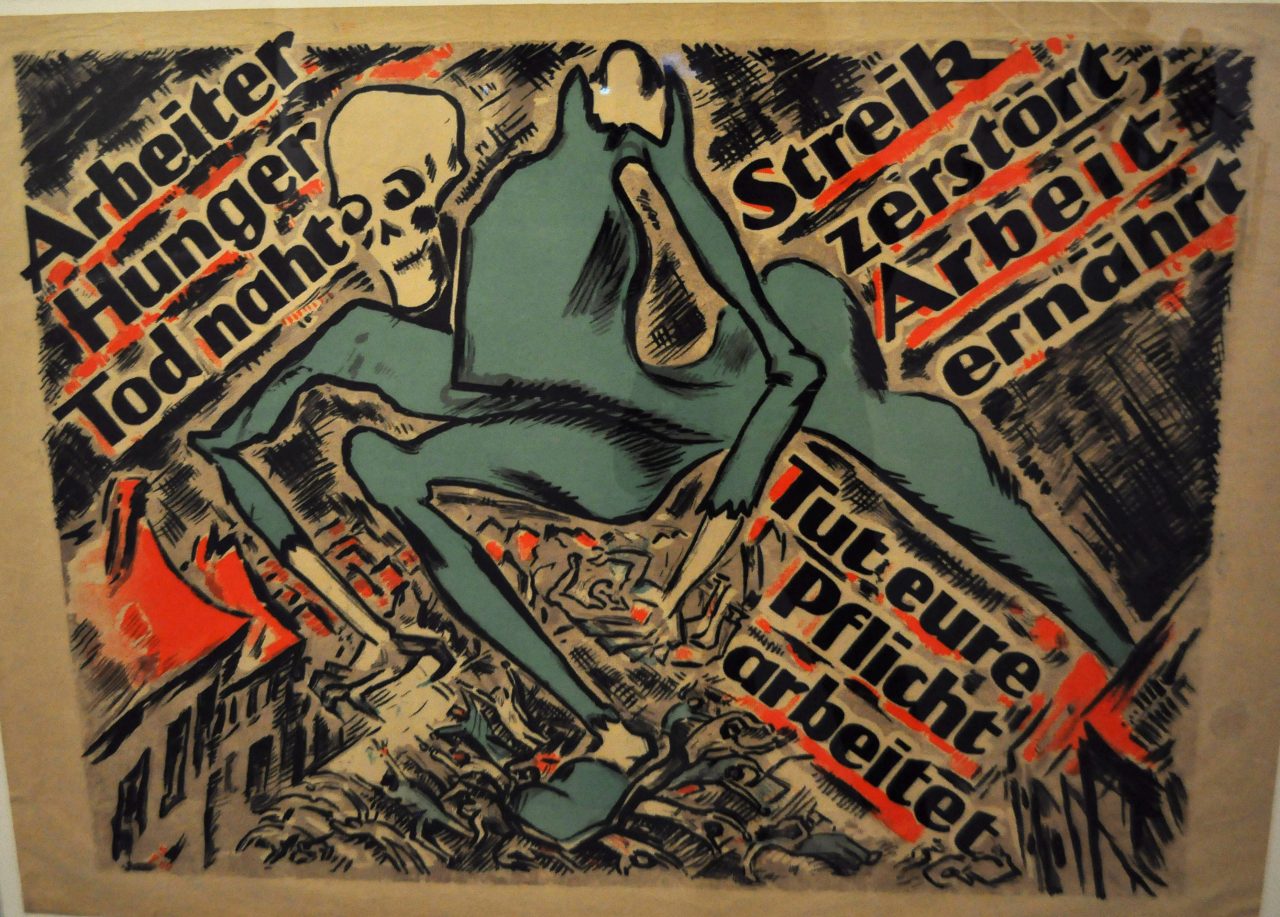

A council of People’s Deputies was installed as a transition government. The Werbedienst, the information unit of the “German Socialist Republic” was tasked with printing posters and leaflets urging people to vote for a National Assembly in January 1919 and to observe peace and order. The design for these promotional tools was taken on by the Expressionist artists. Among them (also Werbedienst staff) were members of the Novembergruppe.

This dramatic poster by Heinz Fuchs (below) uses image and text to illustrate the possible consequences of threatened strikes in the immediate aftermath of the war. The people between houses are being crushed under the feet of a giant figure of Death. They cannot escape its clutches.

Some other examples:

Do not strangle the young freedom through disorder and fratricide, otherwise you shall starve your children.

Or another one: “Unite to the National Assembly!”

“Liberating energies of the new art”

With the German Empire consigned to the past, artists in the Novembergruppe sought to play an active role in defining a new society. The key, in their eyes, was the “closest possible mingling of the people and art”.

A sense of euphoria at starting afresh permeated the association’s earliest displays at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition. In 1919 this state-sponsored show opened up to the avangarde for the first time. Until 1922, the Novembergruppe section was dominated by a mix of Cubism, Futurism and Expressionism. The “liberating energies of the new art” (Adolf Behne, 1919) were seen by many intellectuals as a powerful expression of the new era.

And yet most of the visitors who flocked in their thousands every year to the Glass Palace near Lehrter Bahnhof were disturbed by the art the Novembergruppe chose to display. The dynamic styles were associated with the chaos of the revolution and the crisis-prone republic. In terms of theme, however, these paintings and sculptures were primarily cosmic or religious.

For example:

Right: Karl Völker, 1919, Birth

Fritz Stuckenberg, Schwüle, Sticky Air, 1919 (below)

Moriz Melzer , Blessing, 1917-1922

The artist Moriz Melzer assembled painted slats over the canvas so that the motif changes appearance as the viewer moves around in front of the painting. The work shows a mother and child bathed in rays of light, bright colours and shapes – a religious scene referencing the Christian theme of the Virgin Mart an her infant son Jesus. Experiments such as Melzer’s slat painting were a regular fixture at exhibitions by the Novembergruppe. The title “Blessing” alludes to the power of salvation that many artists saw in art. In their view, it was a force capable of renewing humanity and with it, society.

Georg Tappert, Komposition I, 1919

This painting by Georg Tappert was on display at the very first show by the Novembergruppe in 1919, which was a section at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition. The Late Expressionist scene is reminiscent of the Garden of Eden. In style and content the work is typical of the group’s early phase. Religious intensity and mystic, cosmic fantasy were major features at the time, reflecting the quest for a new human personality and a new society. Tappert was one of the leading figures behind the creation of the Novembergruppe. Between 1919 and 1931 he exhibited with the group on at least 10 occasions. For many years he was active on several of its committees.

Otto Freundlich, The Marks, 1920

Otto Freundlich was a founding member of the Novembergruppe and at the same time one of its most outspoken critics. The association had pledged to serve the revolution in art, and in his view its activities were too apolitical. He called for a “cosmic communism” and left the group again in 1919.

In 1921, encouraged by his friend Raoul Hausmann, Freundlich contributed his portfolio “The Marks” to the Novembergruppe section at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition.

The six prints depict an abstract cosmic setting inhabited by spirit beings and seemingly helpless human figures.

Curt Ehrhardt, The Coffee Grinder, 1920, mixed media

Georg Scholz – several works

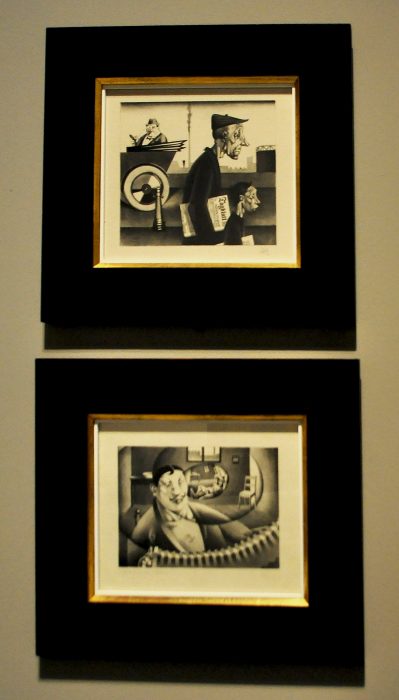

Scholz’s work reminds me in a certain way of Shaun Tan’s aesthetic, especially the “Newspaper collectors” piece (Do watch, for example, Tan’s The Lost Thing).

Upper: Newspaper Carriers / Lower: Der sentimentale Matrose

The Lords of the World, 1922

Industrial Farmers, 1920

In 1921 Georg Scholz wrote an article for the Novembergruppe magazine `NG` attacking art that is merely aesthetic. The artist put his principles into practice by portraying a bigoted, money-grabbing family of farmers. The caricatured painting is reinforced by various elements of collage pasted onto the picture.

Scholz was inspired to try this technique by the Berlin Dadaists, with whom he fostered close links. When the Novembergruppe presented this work at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition in 1921, a few conservative politicians accompanying the President of the Reich on his tour of the shot left the room in disgust.

Walter Kampmann, The Commander, 1922

Dada & Scandal

At the Great Berlin Art Exhibition in 1920 the Novembergruppe section included Dada. These works provoked a scandal. With their pasted press cuttings and everyday utensils, they constituted a radical attach on artistic tradition. Reviewers ragged at this “dunghill art”, all the more as the exhibition was financed from the public purse.

In response to these accusations, the Ministry of Culture threatened to exclude the Novembergruppe in 1921. Under pressure from the exhibition managers, the association therefore removed two brothel scenes with socially critical content. Other provocative works like Georg Scholz’s “Industrial Farmers” were kept in the show – and again prompted outrage.

The concessions that had been made angered artists from the Dada entourage. They accused the group of caving in to censorship. In their eyes, the association was not political enough so they resigned. It was an acid test, but the association emerged all stronger> from 1922 onwards the press and public were more relaxed and increasingly positive about Novembergruppe exhibits.

Arthur Segal, Heligoland, 1923

Arthur Segal was intrigued by optical phenomena. His “prismatic” painting takes its cue from the way light is broken up to produce spectral colours. He was at pains to give equal treatment to three basic components: shape, colour and light. This work represents the island of Heligoland. The entire picture, including its frame is covered by a grid.

A reproduction. Source: Amazon.

Each field is autonomous and yet part of the overall motif, which has been reduced to patches of colour and geometric forms. Segal filled out the boxes with subdued shades that shift gradually from dark to light. In 1924 Segal showed two similar versions of Heligoland in the Novembergruppe section at the Great Berlin Art Exhibition.

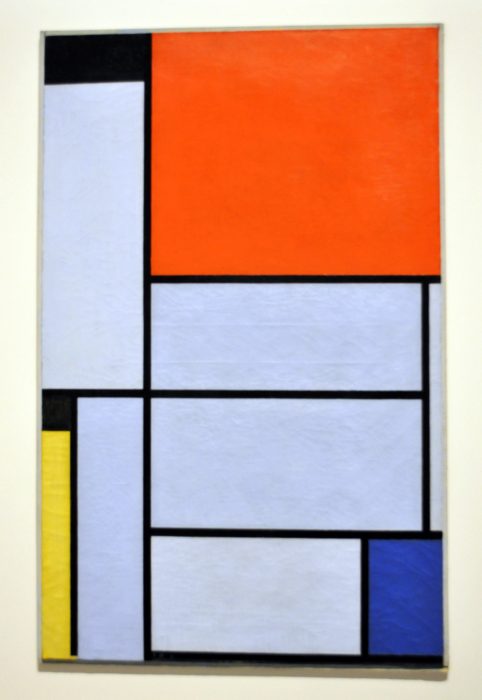

Piet Mondrian, Tableau I, 1921

Read more about the work here.

Walter Dexel, Composition 1923 IV

Walter Dexel’s works are completely detached from the figurative world. His abstract compositions consist of colourful geometric forms that structure the picture space and maintain a careful equilibrium.

At Novembergruppe exhibitions Dexel’s painting were hung together with works by Russian abstract painters and the Dutch De Stijl artists Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg. Dexel’s own formal idiom was inspired in many ways by their principles of composition.

Some more works of Dexel’s here. This Bottrop sculpture is also worth taking a peak at.

Construction and Objectivity

The Novembergruppe was open to experiment and championed Modernist art in every variation. Its exhibitions were a major public platform for the ground-breaking trends of the times. The First World War had suspended interaction between German artists and the European avant-garde. The association therefore made every effort to revive international contacts.

From 1922 it attached clear priority to the latest abstact styles from Eastern Europe and the Netherlands. Regular exhibition guests were the Russian Constructivists and the Dutch De Stijl movement, whose radical rebuttal of figurative art provided important inspiration for German artists.

Styles at the other end of the spectrum were also welcome: many artists were moving on from Expressionist beginning to a new kind of realism that was later dubbed New Objectivity.

Issai Kulviansku, Lithuania, My Little Daughter Kiki, 1927

This portrait shows the daughter of the artist Issai Kulvianski. The work was exhibited in 1927 and again at the Novembergruppe’s jubilee show in 1929. The everyday scene is offset by a surreal atmosphere. The red ball slipping out of the girl’s hand remains mysteriously suspended in mid-air.

The distortion of spatial perspective and the oversized figure of Kiki were among the stylistic devices used by New Objectivity. Within an apparently sober, objective depiction, strange and disturbing details emerge to reflect the alienation and crisis felt by people in the modern world.

Absolute Film

In May 1925 the Novembergruppe also became a forum for experimental film in Germany. Projects around moving images were shown to a full house in the 900-seat UFA cinema on Kurfurstendamm at an event called “Absolute Film”. On the programme were abstract and surrealist avant-garde works by German and French film-makers, among which Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack, Hans Richter and Fernand Leger.

Ballet Mechanique, Fernand Léger, Dudley Murphy

Absolute film dispensed with a narrative film structure, relying entirely on the visual effect of rhythmic movements and abstract shapes and colours. The aim was to create “music for the eye” (Viking Eggeling) or “painting with time” (Walter Ruttmann). There is a close affinity with abstract trends in the fine art exhibited by the Novembergruppe.

Hans Richter, Rhythmus 21

Hans Richter – Film Ist Rhythm: Rhythmus 21 (c1921) from Avant-Garde Cinema on Vimeo.

Hans Richter, Filmstudie 1926

The New Architecture

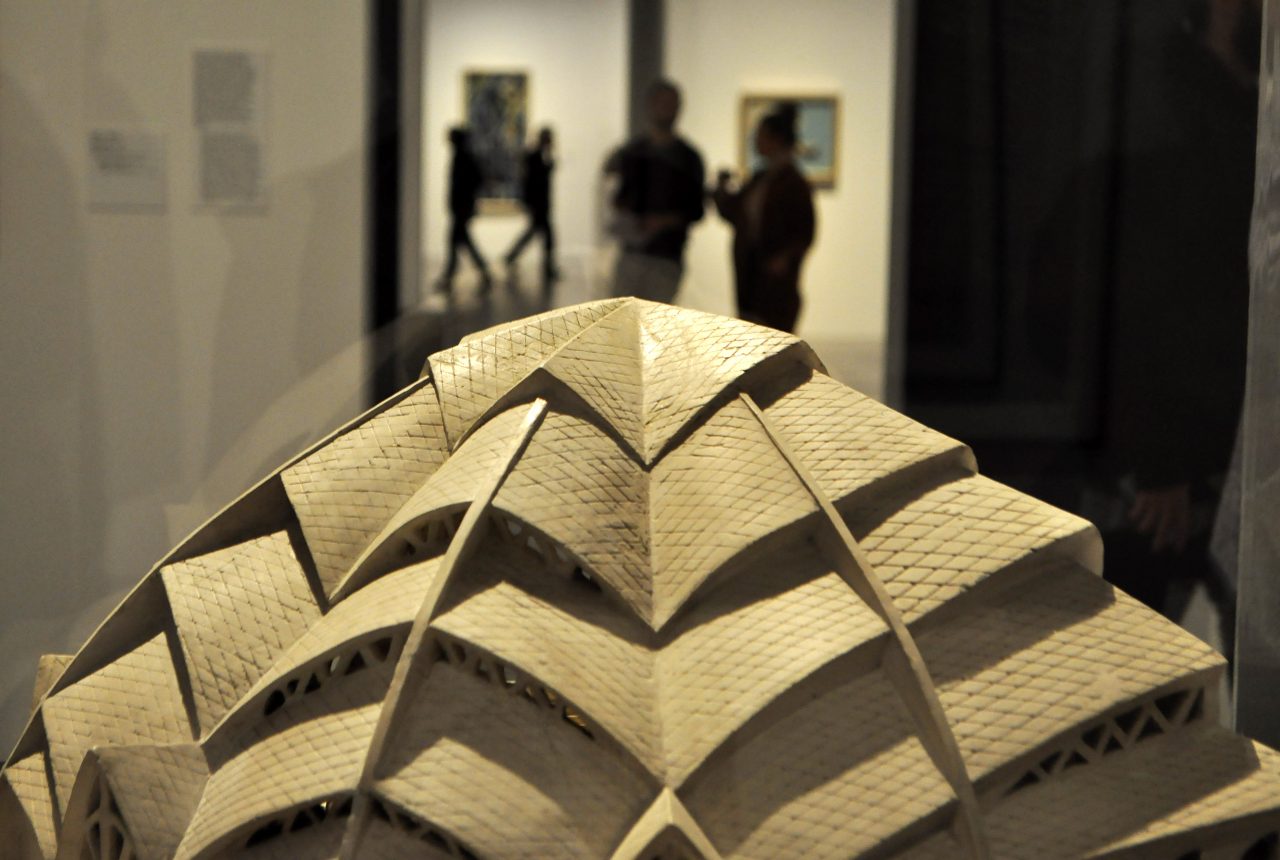

From 1922 more and more architects joined the Novembergruppe, which became a key forum for Neues Bauen. This functional architecture favoured clarity and simplicity in its formal idiom. Designes and models for skyscrapers and road infrastructure were among the numerous projects exhibited by the association. The inflation years until 1924 meant that most of these ideas could not be implemented. The construction industry was in the doldrums and there was little work for architects. During this difficult phase Novembergruppe shows proved to be an important vehicle, allowing these architectural visions to maintain public visibility.

From 1923 the architects in the Novembergruppe even organized separate rooms in the group section at the annual exhibition. This enabled them to highlight their projects independently of the visual arts. The press was especially enthusiastic about these displays, but there were tensions within the association as a result. In early 1927 almost all the architects left. From this point on, the Bauhaus and the architects’ association Der Ring provided a new home for Modernist ideas about building.

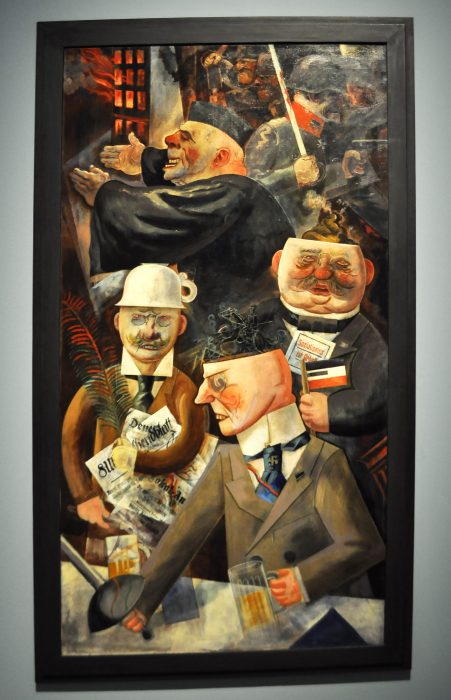

George Grosz, Pillars of Society, 1926

In earlier days George Grosz had called for more political commitment from the Novembergruppe. He did not join the association until 1927, when it had begun to show more examples of social criticism. The title of this work, “Pillars of Society”, is polemical. Grosz is satirizing reactionary forces who posed a threat to the young republic: the journalist, the clergyman, the lawyer, the politician and the army officer – caricature exposes their hostility to democracy.

Although the organisers of the Great Berlin Art Exhibition were essentially liberal-minded, they threatened not to allow this work, but by putting up a united front the Novembergruppe managed to avoid censorship.

A Belated Revolution

From the mid 1920s the significance of the Novembergruppe gradually waned. There was growing public acceptance for Modernist art, which had gained many footholds in the lively Berlin art scene. To reassert its role as an influential association of artists, the group now adapted its strategy.

In the past, it had always resisted co-optation for political ends, insisting that its only commitment was to revolution in art. Now, it devoted more space to works with a critical social content and highlighted its roots in the November Revolution, the source of its programmatic name.

For its tenth anniversary in 1928 the association tried to muster all its forces again. With a copious publication and a big gala exhibition, it assertively took stock of its accomplishments and swore a new oath to the social impact of art. By this time, however, many of the Novembergruppe’s objectives were widely considered to have been overtaken by history.

Conrad Felixmuller, The Agitator, 1946

Conrad Felixmuller’s painting “The Agitator” shows the communist politician Otto Ruhle (1874-1943) addressing workers in Dresden. The original (destroyed) was reproduced in the publication to mark the tenth anniversary of the Novembergruppe and exhibited at the anniversary show in 1929.

Felixmuller was a founder of the Dresden Secession, which affiliated to the Novembergruppe as a local group in 1919. In 1920 Felixmuller left both organization. As a member of the Communist Party he disliked their political moderation. Only in 1928 did he rejoin the Novembergruppe, when it had begun to focus on works that were socially critical and referenced the revolution.

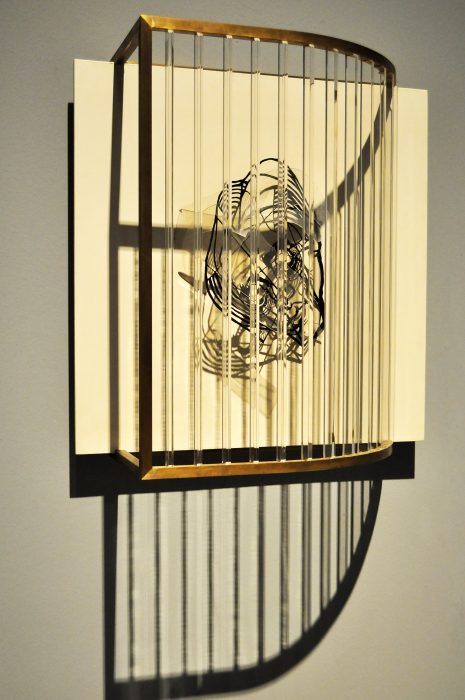

Walter Kampmann, Portrait of My Wife, Ether Mask, c. 1930

Walter Kampmann liked to test the boundaries between painting and sculpture by experimenting with new materials. In this portrait of his wife Frieda he included plastic, an unusual material to find in visual art at the time. The face made of zinc sheet resembles a drawing in space. The subtitle “Ether Mask” was a reference to the anesthesia masks in use at the time, but also to the philosophical concept of ether as the primal stuff of life.

Kampmann came to Berlin in 1919 to teach at a college of higher technical education for the textile and garment industry. From 1921 he was a dedicated member of the Novembergruppe, taking part in its exhibitions until 1932.

An Enforced Ending

From 1930 the Novembergruppe began falling apart and confronted financial difficulties. Fewer artists took part in its exhibitions as the Great Depression destroyed professional livelihoods. The works on show during this period reflect a detachment from reality and emotional withdrawal.

The circumstances that precipitated and end to the Weimar Republic did not renew the group’s political spirit. Nor was the situation reflected in motifs or techniques. After the Nazis took power, the Novembergruppe was denigrated for “Cultural Bolshevism”. From 1933 it was no longer admitted to the Great Berlin Art Exhibition, and in 1935 it was struck from the register of associations at its own expense. The art of many former members was labelled “degenerate”. Their works were removed from public collections.